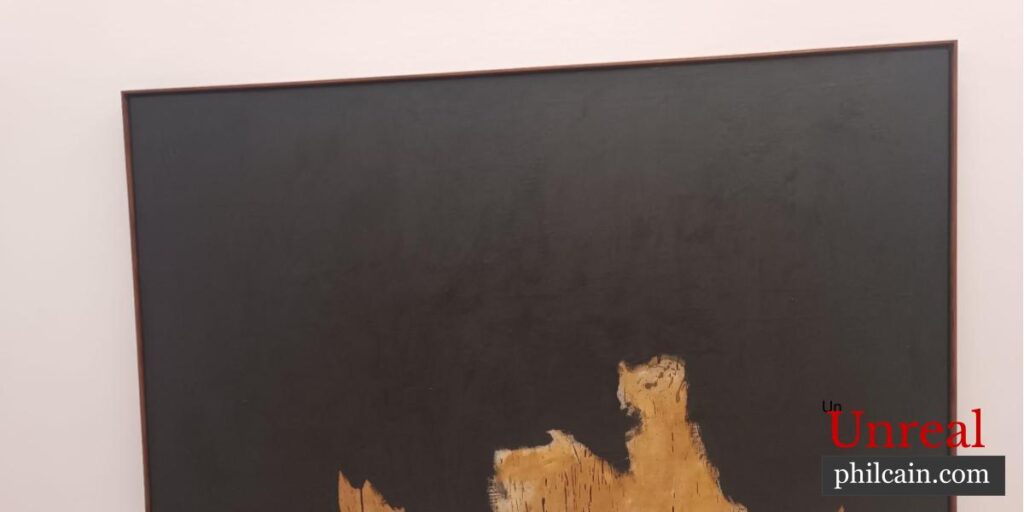

This is fiction written in an hour with the Sunday Writers’ Club at an exhibition of work by abstract expressionist Robert Motherwell at Vienna’s Kunstforum with the prompt. “While wandering the gallery you notice another visitor who is crying. They stand, transfixed, staring at a painting as the tears stream down their cheeks. You approach this person to make sure they’re OK.”

It seemed wrong to intrude on what was clearly a painful and private moment when I first passed. But she was still there as I was about to leave the gallery twenty minutes later, alone, rooted to the spot, visibly upset.

It seemed wrong not to at least ask if she was okay. That plus she was somewhat attractive. I did my best to approach the painting and stand beside her, as if by accident. She turned to me sharply, as if to ask what I was doing standing there. I was clearly not very convincing.

“A very moving picture. Very moving indeed,” I said solemnly.

“Moving? What the fuck do you mean? It’s not moving anywhere, it’s a fucking painting.”

Her voice did not match my expectations. How could someone so rough hewn be so affected by a painting. It must be a working class pretence she had adopted at art school and not shaken off.

“I-I mean, you know, moving, it’s emotionally affecting, it stirs the feelings, moving in that sense,” I warmed to my theme. “Is the viewer not compelled to feel a deep pang of sadness for the heroic patch of brown so vainly fighting against the prevailing blackness? Are there not echoes of the dark chaos engulfing the ochre earth of the Iberian peninsula only two decades before?”

“Oh, right, yeah. That kind of moving. I had never really thought of it like that,” she said, angling her head to try to see what I was talking about.

“You didn’t? How can you say that when you’ve been observing the painting for so long, weeping?”

“Oh, yeah, that. That’s a bit, well, complicated. I work in the caff here and can’t be seen talking to customers. But buy me a coffee round the corner in ten minutes and I’ll tell you.”

This meeting seemed unlikely to be the exchange of artistic sensibilities I had been in search of, but I agreed.

She told me that years ago her mother had given her an old painting on board. It was a picture of a cottage surrounded by trees with a woman picking apples in the sunshine. Two children in white smocks were playing with a wooden toy in the long grass.

Her granddad, Sid, had picked it up at a flea market. Then her mum had passed it on to her as a parting gift when she first left home to start work in a London department store.

“Here you are, love. This’ll keep you feeling nice and snug in your new place,” her mum had said. She did her best to look grateful, but she hated it. It was so twee and saccharine, not at all her thing.

“What the fuck does a 20-year-old do with an old painting? At that age you’ve not got a clue.”

Still, she had packed it into the back of the car with her pots and pans, to please her mum.

Then her mum phoned to say she had seen a picture just the same on one of the antiques programmes. It had gone for a little short of £50,000. And she was right, it did look just the same. On her way to work in the gallery cafe she had seen Iberia No 2.

It reminded her of the night years ago when she and her flatmates had taken a spatula and white spirit to the picture. Laughing they had scraped away the thick layers of cracked and flaky paint. There was just a bare board where once there was a country cottage, a woman and two little children. ■